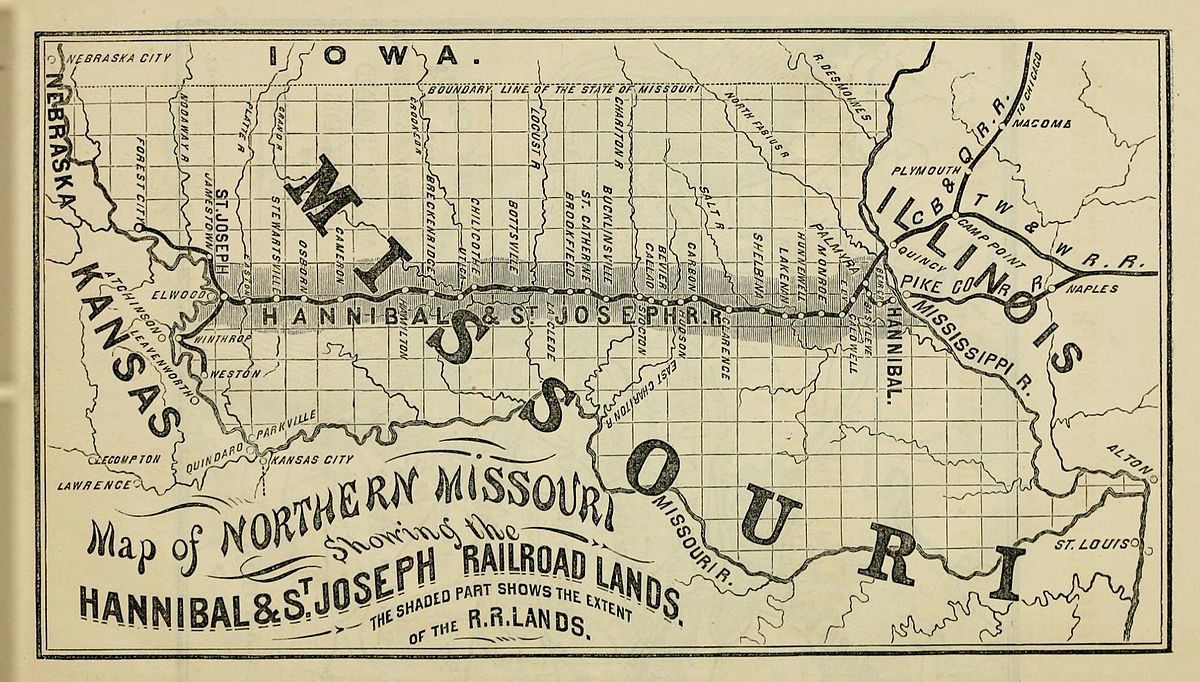

The Hannibal & St. Joseph railroad, the first to cross Missouri, started at Hannibal in the office of John H. Clemens, father of Mark Twain. This meeting was held at Hannibal in the spring of 1846. Z. G. Draper was chosen president, and R. F. Lakenan, secretary. At the next session of the legislature, in 1847, the charter was obtained. Then followed enthusiastic meetings and conventions all along the proposed route. And then the movement slumbered until 1850. In 1851 the legislature began the voting of bonds on condition that the company raise and expend corresponding amounts. The counties and the towns voted bonds. That was the method of railroad financing in Missouri before the war. In the fall of 1851 ground was broken at Hannibal with a great procession, much oratory and bell ringing and cannon firing. The next year Congress voted 6oo,ooo acres of good land in aid of the road. Contracts were let but construction dragged. It was not until February 13, 1859, that the first through train ran. The rate was five cents a mile and some times more for passengers. The road was known in Missouri as “Old Reliable.” The Hannibal & St. Joe was started from both ends. It was completed in Munipower’s field two miles east of Chillicothe at seven o’clock in the morning of February 13.The junction of the two ends was celebrated by the transportation of several barrels of water from the Mississippi at Hannibal to St. Joseph where the barrels were emptied into the Missouri. This, as the orator said, typified the union of the two great water courses of the American continent.

The original idea of the Wabash was a railroad from St. Louis and St, Charles northwesterly along the dividing line between the Mississippi and the Missouri river valleys to the Iowa line and thence to Des Moines. The name was the North Missouri. This road was chartered in 1851 and reached Macon in 1859. Not until 1864 did the North Missouri take over the two shorter roads, the Chariton and the Missouri Valley and build through to Kansas City.

When Paramore built 700 miles of three-foot gauge road through Missouri and Arkansas and into Texas with only $12,000 a mile bonded debt, it seemed as if standard roads with larger indebtedness could not compete. There was much sentiment in St. Louis favorable to the narrow gauge idea. But it died out and the narrow gauge became standard. Samuel W. Fordyce, first receiver and then reorganizer of the Cotton Belt, as the road was called, worked out the railroad problem demonstrating that a standard gauge was best.

Source: Centennial History of Missouri